Gifts From The Past

Depression-era Christmas presents were few and practical

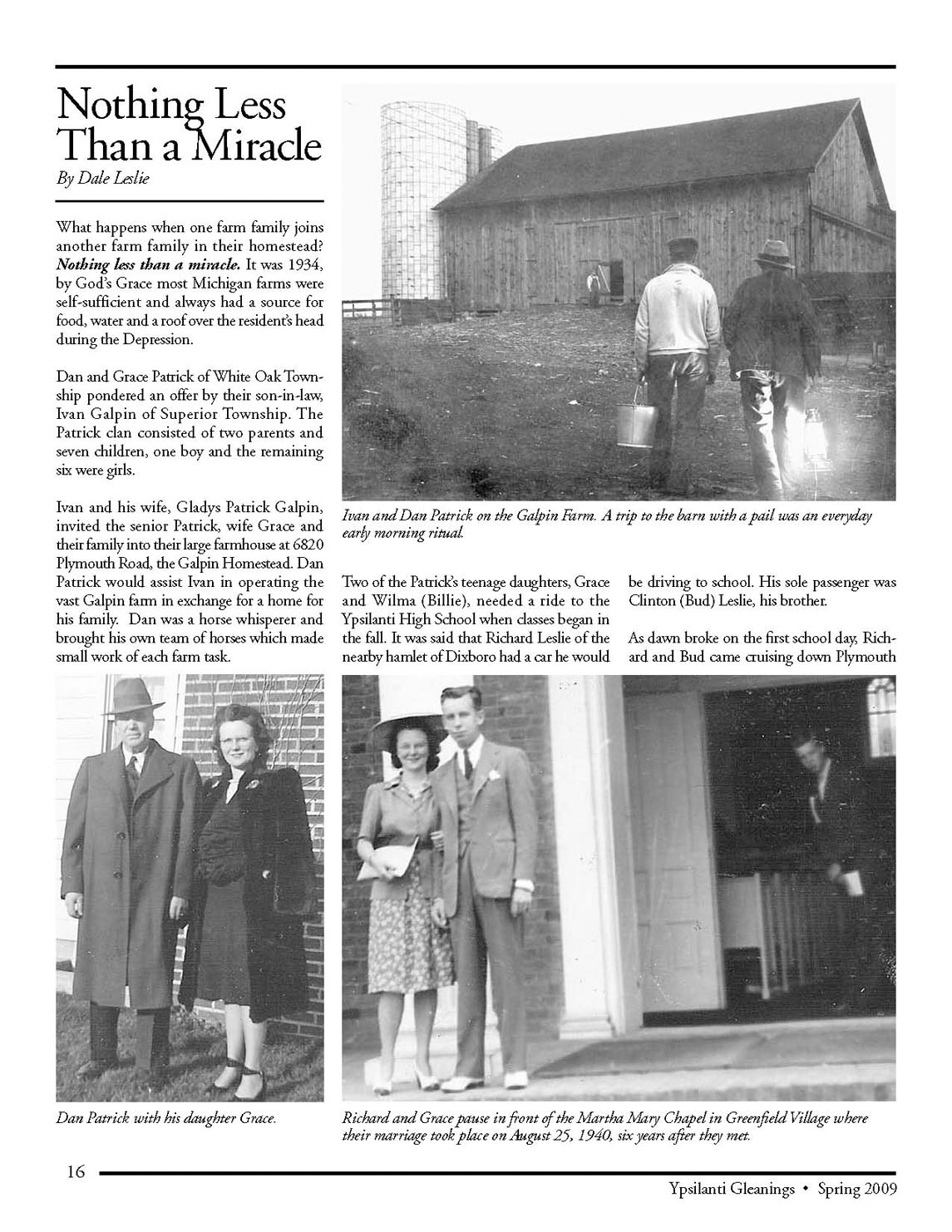

In the years of the Great Depression before World War II, gift giving did not dominate Ann Arbor Christmases as it does today. "You were lucky if you got one present," recalls Bob Ryan of his childhood. "I'd get an orange in my stocking or sometimes an apple. One year I got a sled."

"Presents were primarily clothes," recalls Lois Uhlendorf McLean. "We'd get practical things: school clothes, a sweater, what we needed." Though parents bought necessities, sometimes other relatives would give toys like dolls or trucks. She also recalls that sometimes her dad would buy a new Christmas tree ornament and say it was a gift from the family to the tree.

Harlan Otto remembers looking forward to the hard candy that came in a special box every year from St. Paul's Church. He also recalls many handmade gifts, such as mittens and socks. "Grandma Zill, it seemed like she could do it in twenty minutes. She'd say, 'Oh, you don't have any mittens.' Zoom, zoom, zoom, she'd make them."

Some parents put a great deal of creativity and resourcefulness into making presents. Otto remembers receiving toys made out of old spools from thread, while Coleman Jewett recalls receiving scooters made out of old skates.

Maybe because presents were such a rarity, people now in their seventies and eighties seem to have remarkable memories of the ones they did get. Otto recalls two very clearly: a flashlight he got from a neighbor, and a steam shovel that his godfather gave him and that he "played with forever."

Rosemarion Blake recalls a life-changing present: "Mrs. Blackburn—she worked at Barbour Gym—thought it necessary for kids to read, so she always gave me a stack of books." As a result of this yearly gift, Blake became an avid reader.

Both Coleman Jewett and John Hathaway recall "little big books," which had pictures on the borders so that when you riffled the pages you saw the figures move. Inexpensive hardcover books, such as adventure stories for boys and Nancy

Drew for girls, were other popular presents. A favorite gift with Mary Stevens Hathaway and her siblings was a yearly subscription to Life magazine, given by an aunt and uncle.

Back then toys were powered by imagination, not batteries. Pat Murphy remembers getting a doll in the pre-Barbie days that came with material for miniature clothes that she had to make herself, using a sewing kit that was also included. Jewett remembers getting art supplies, such as watercolor sets or a compass to draw circles.

Erector sets and their cheaper cousin, Meccano sets, were a big hit with boys; they could add to their collections each year, as they did with painted tin soldiers. With the days of political correctness still in the future, boys also got more macho presents, such as high-top boots with a slit on the side for a jackknife. Jewett remembers getting cap guns to play cowboys and Indians with; when he was about eleven years old, he got a Red Ryder BB gun, made in Plymouth. Bob Kuhn remembers receiving boxing gloves complete with a punching bag. In contrast, all of the women interviewed remember getting dolls.

Al Gallup gets the prize for the most unusual present—a puppy. "One year I got a Manchester terrier we named Boots," he remembers. Boots went on to claim fame after his picture was featured on Scott lawn products distributed nationwide, according to Gallup. Why was Boots so special? "Because he dug dandelions," Galiup says. "He pulled the roots out but didn't eat them. We never knew why."

Photo Captions:

Grace Stevens TerMaat, Brad Stevens, and Mary Stevens Hathaway, Christmas 1937.

Coleman Jewett, junior commando, 1943.

Brad Stevens plays with his new train set, 1931.

The West Side Dairy

From creamery to music

Two connected buildings at 722-726 Brooks, nestled at the back of a driveway in a residential neighborhood, are puzzling to people passing by unless they know it was once a family-run dairy. The front part was constructed in 1919 and the large part in back in 1940. Brothers-in-law Adolph Helber and Alfred Weber owned and operated the West Side Dairy for thirty-four years, delivering fresh dairy products to city residents until 1953.

Adolph Helber, born in 1886, grew up in a large family on a farm on Dexter Road in Scio Township. He left school in the seventh grade, not uncommon at the time, and worked as a hired farmhand until 1904, when he went to work delivering milk for Jake Wurster, a brother-in-law. Wurster's dairy was on the corner of Catherine and North Fifth Avenue.

When Helber started in the dairy business, milk was still sold "raw," or untreated, fresh from the cow. (Although pasteurization equipment, developed to kill milk-borne infections, was available in the 1890s, it hadn't yet been universally adopted.) The raw milk was stored in a big tank at the front of the horse-drawn delivery wagon and scooped out into a pitcher or milk can supplied by each customer on the route.

In 1912 Helber married Alma Weber, the sister of a fellow driver, Alfred Weber. The Weber family house was at 809 Brooks, then the last residential street off Miller. Alma and Alfred's father, Jacob, owned much of the land in the area. In 1914 the Helbers moved to 720 Brooks, and in 1919 Helber and Alfred Weber opened a dairy out of a small one-story cement-block building they built in the Helbers' backyard. Milk was supplied by Helber's brother Carl, who had stayed on the family farm, and also by the Seyfried and Hanselman farms.

Helber and Weber started their days at 4 a.m., feeding and harnessing the horses. They delivered milk in the morning and in the afternoon pasteurized and bottled it for the next day. Because neither the farmers nor the customers had good storage, the partners accepted and delivered milk seven days a week. Their only time off was Sunday afternoon. Their wives, Alma Helber and Rose Weber, ran the office, did the bookkeeping, handled over-the-counter sales, and helped with production.

In the days before cholesterol worries, dairies competed for the richest milk the farmer had. Before homogenization, customers could see at a glance how rich the milk was by the thickness of the cream on top. (Narrow-necked milk bottles were developed to exaggerate the visible cream.) The West Side Dairy made skim milk (or buttermilk) only as a by-product of butter making, selling it back to the farmers for a penny a gallon as feed for their pigs and chickens.

As the number of their customers grew, Helber and Weber were able to hire help, giving priority to relatives. The delivery men included Eddie Weber, Alfred's brother, whose route included what is now known as the Old West Side; Leon Jedele, Rose Weber's brother; and Henry Grau, who was married to Alma's sister Clara. After relatives, neighbors were hired. The employee who probably lived the farthest away was Fred Yaeger, who walked to work every morning from his home on Pauline.

The family employees built houses in the neighborhood near their work. Alfred Weber's neighbor, Will Nimke of 827 Brooks, built him a house at 730 Brooks. Eddie Weber lived at 727 Gott, where he grew wonderful dahlias. When the Helbers' sons grew up, they lived in the neighborhood, too, Erwin at 706 Brooks and Ray at 725 Gott. Jacob Weber owned and rented other houses, one at the corner of Brooks and Summit and three others on Gott Street, right behind the dairy. Weber and Helber owned the house between their two houses and rented it to the Moon family. The Weber property also included a big field west of the house, where the horses sometimes grazed.

Making deliveries, the milkmen would walk along the sidewalk as the horses plodded alongside them in the street. Sam Schlecht, who helped out on the routes as a teenager, recalls that the horses "knew more about the route than the human beings." If milk was delivered on a dead-end street, the horses would turn around while the men delivered to the last houses. If the milkmen cut through a backyard to deliver milk on the next street over, the horses knew to meet them there. Schlecht remembers that at the end of the route, as they went down Chapin toward Miller, the horses would pick up their pace, eager to get home for their oats and hay. When Helber and Weber switched to trucks in 1934, the milkmen found them a mixed blessing. They no longer had to feed and harness the horses each morning, but their routes took them longer without the horses' help.

Deliveries were made every single day except Christmas and Thanksgiving. On the day before those holidays, the milkmen would go around twice, in case a customer had forgotten anything that morning. Henry Michelfelder, a relative of Leon Jedele's, remembered that if his family ran out of something during the day, they could call the dairy and it would be brought over.

The milk and cream delivered for sale by retail stores was very fresh, since every day the milkmen would take back any that wasn't sold. The day-old products were used to moisten the cottage cheese the dairy made. In the 1940's, when refrigeration had become common, the dairy scaled back to three deliveries a week. Marian Helber, Ray's wife, remembers that "people had a fit. They thought they needed fresh milk every day for their coffee or cereal."

Erwin and Ray Helber grew up working in the dairy part-time and summers. After graduating from Michigan State Normal College (now EMU), Ray worked bottling and also delivering. During World War II he left to work at King Seeley (he learned of the job opening because the plant was on his route) and ended up staying there until 1975, when he retired. Erwin stayed at the dairy, gradually taking over more of the responsibility from his father and uncle. In 1953, when the brothers-in-law retired and sold their business to United Dairies (later Sealtest), Erwin stayed with the new owners, eventually moving to Flint with Sealtest.

Today the buildings looks similar from the outside but have totally new uses inside, mostly related to music. Four Davids (Orlin, Sutherland, Collins, Peramble) between them teach or repair guitar, violin, pianoforte, and piano. The neighborhood is also filled with evidence of the dairy for people who know where to look: a four-car garage (used for delivery trucks) at the corner of Summit and Brooks, a barn at 809 Brooks (later used for a construction business), and a big lot at 827 (now a big private garden). After the dairy moved out, tenants included a sugar packing manufacturer and a bookbinding operation. In 1964, Robert Noehren, a U-M organist and a pioneer in the organ revival movement, rented it for a pipe organ factory, presaging its present use. The field behind the Weber house is now the site of the Second Baptist Church.

[Photo caption from book]: The West Side Dairy in the mid-1930s. Left to right: Henry Grau, Alfred Weber, Eddie Weber, Adolph Helber, and Leon Jedele. All are related by blood or marriage. The dairy had just switched from horse-drawn milk wagons to trucks and was experimenting with various models-three different makes are visible.

“Courtesy Paul Helber”