Traveling the Chain of Lakes: When Trains and Water Taxis Ruled

At rush hour the railroad underpass in Dexter turns into a bottleneck, as people who live north of the village come and go on their daily commute. Many of them live in lake homes, either converted cottages or new houses, on the Huron River’s Chain of Lakes. In contrast to today’s solo road warriors, a century ago families took a slower but more leisurely trip by train and water taxi to reach lakeside cottages and hotels.

The six lakes in the chain—starting at Zukey, through Strawberry, Gallagher, Whitewood, Base Line, and ending at Portage—are all fed by the Huron River. The Huron starts north of Milford, flowing west until it reaches Portage Lake, where it turns east and south and eventually spills into Lake Erie. The Chain of Lakes is at the end of the western-flowing stretch and comprises larger bodies of water connected by narrower ones. “The change of scenery from lake to river and river to lake was beautiful beyond description to a lover of nature,” wrote Eli Moore in 1907, recalling an 1877 rowboat trip he took from Portage, where he was camping, to Zukey.

The lakes at each end of the chain, Zukey and Portage, are off to the north side of the river, but are connected to it—by Devil’s Basin at Zukey and by a canal at Portage that was deepened and widened in 1928. Scott Strane, who’s at work on a book tentatively titled What Is a Zukey?, thinks that the name comes from the Chinese words for the crescent moon, though he admits uncertainty about how a Chinese name would have arrived in nineteenth-century Michigan. Rick Glazer, co-owner of the Zukey Lake Tavern, believes that the name is of Native American origin.

Early French explorers gave Portage its name. It was here that they left the eastward-flowing Huron River watershed, carrying their canoes overland to connect to the westward-flowing Grand River. “An English explorer named Hugh Heward did the trip in the early eighteenth century that some folks re-created a couple of years ago, eventually traveling all the way to Chicago along the [Lake] Michigan shoreline,” explains land protection consultant Barry Lonik.

The river connections spurred the lakes’ development as a recreation area, giving people vacationing on any one of them a wider choice of places to explore and enjoy than if they were limited to a single lake. As early as 1836, an actor named Gardner Lillibridge dreamed of developing a “Saratoga of the West” on Portage Lake, modeled on New York’s Saratoga Springs resort. Key to his plan was a steamboat for pleasure parties that would make a round trip from Portage, Base Line, and Strawberry lakes through what the 1881 History of Washtenaw County described as “the most romantic and delightful scenery ever seen in this or any other country.” Lillibridge’s ambitious plan included a lookout on what is today known as Peach Mountain (site of the U-M’s radio telescope), so visitors could see the grand view of the lakes below. He platted a quarter section of land into 125 lots, giving his streets names such as Dryden, Byron, Shakespeare, Haydn, and Mozart. If none of those streets is familiar, it’s because Lillibridge managed to sell only half of one lot.

Unlike Lillibridge, most of the area’s early settlers did not consider having a lake on their properties an advantage. They were farmers, and neither the lakes nor their marshy shores could be planted.

The pioneers who did end up with lakefront acreage made the best of the situation, sometimes cutting wild marsh hay for feed before they had time to put in a better crop, and in winter cutting and storing lake ice. Occasionally passersby would pay them for permission to take a swim or to camp on the lakeshore, but at that time roads were just Indian trails or at best wagon trails, so access was difficult. “Very few, if any, cottages, were to be seen along the banks as I remember, but now and then a ‘tent,’” wrote Moore of what he saw on his 1877 boat trip.

This changed after 1878, when the Ann Arbor Railroad reached Whitmore Lake and Lakeland (the village on the north end of Zukey Lake), opening up these two communities for vacationers from the Ann Arbor and Toledo areas and beyond. Train passengers could stay at hotels or cottages or come just for the day. Daily traffic got so busy that during the interurban railroad bubble at the turn of the twentieth century, there was talk of laying interurban tracks from Lakeland to Ann Arbor—a competitive threat the Ann Arbor Railroad blocked by running a gasoline-powered McKeen motor car on its own tracks. Nicknamed “the ping-pong,” it ran back and forth between Ann Arbor and Lakeland eight times a day from 1911 until 1924.

Once people got to Zukey Lake, they could access the rest of the chain by boat. Steam-powered passenger boats began running in 1897. The first steamer was named the Prudence Potts, after the daughter of its owner, J. W. Potts. In the 1920s Potts advertised that he also had camping sites available on three of the lakes.

Once internal combustion engines became reliable enough, people quickly switched to them, because they didn’t blow up like steam boilers could. For instance, Karl Guthe, U-M professor of physics, and his wife, Belle, used a “motor launch” to bring visitors to their cottage on Strawberry Lake; a 1917 photo shows one such guest, their niece Dora Ware (mother of Ann Arbor physician and historian Mark Hildebrandt). They also used the boat to pick up groceries at the store at Lakeland.

If motor launches were the lakes’ equivalent of limousines, then rowboats were the taxis and rental cars. Rowboat owners met all the trains and could take people directly to their cottages. Some of those arriving would be met by friends who had their own boats, while others rented them for the duration of their vacations. A 1922 promotional book, Valley of a Thousand Lakes, is full of boat ads—for sale and for rent. The Waters’ Pavilion resort in Lakeland promised “Motor boats, row boats and canoes for all,” while Fred Imus, also of Lakeland, offered motor boat livery service as well as boats for sale, explaining that “with twenty miles of navigable waterways open to you a motor boat is a constant source of enjoyment.”

Families who bought lake lots in that era didn’t always build a cottage right away, but often first camped out. Later, after their savings recovered, they built a modest structure, and later a more substantial one. Most cottagers, even if they didn’t own boats, had docks facing the lake so people could come and go on the water.

Base Line Lake also was named for its location—the east-west base line surveyors established for laying out the state runs through it. What is believed to have been the first cottage on its south side was built in the early 1880s by George Wahr, who owned two bookstores in Ann Arbor, and his brother-in-law, Charles Staebler, another Ann Arbor merchant.

The original cottage was one big room, which made staying there not much different from camping—though it did have a pump in the kitchen and a privy out back. The brothers-in-law enjoyed getting away with a group of friends, also Ann Arbor businessmen—the Haarers owned a pharmacy, the Arnolds a jewelry store, and Heinzman had an ice business—to play poker and fish. They later divided the cottage into two rooms so two families could stay together in semi-privacy.

Serious development at Portage Lake started in 1902, when a group of Ypsilanti businessmen formed the Portage Lake Land Company and set up a subdivision on former farmland on the lake’s eastern shore. The next year Pinckney resident Clarence Baugh created Baugh’s Bluff on the other side of the lake. Most of the buyers came from Pinckney, only three miles away. In those days, though, moving out for a summer season was quite a trip by horse and buggy.

As automobiles made travel easier, buyers began to come from farther away. In the 1920s the Chain of Lakes experienced its biggest real estate boom. Valley of a Thousand Lakes is filled with ads for lots, cottages, and resorts that painted lake living in glowing terms. An ad for lots on the eastern shore of Strawberry—“the Queen of Lakes”—assured prospective buyers that a “broad ribbon of hard white beach flanked by a forest of spreading elms and maples, a hard bathing beach suited for the kiddies, the novice and the expert swimmer washed clean by the incoming current of the Huron, all fanned by cool lake breezes, lend charm to this location.”

People who owned cottages often remained all summer—at least the mother and children did, with the father commuting evenings or weekends. During the 1950s, Charlotte Sallade and her four children enjoyed summers at Base Line Lake while her husband, George Wahr Sallade (grandson of George Wahr), continued his law practice in town but drove up every evening. Families who didn’t own a cottage could rent one and follow the same pattern for part of the summer.

Commercial developments, such as hotels and grocery stores, were found at each end of the chain—Portage and Zukey lakes. In 1931 Newkirk Birkett, owner of land on Portage Lake where Lillibridge had once dreamed of a resort, brought in 1,500 tons of sand to develop the Newport Beach Club.

Owned by Tom Ehman since 1966, and now called the Portage Yacht Club, it offers its members a wide variety of activities, including boating, swimming, and dining. When Ehman took over, sailing was the big activity, but today he notes that about two-thirds of the club’s members prefer pontoons or motorboats. Also at Portage Lake is Klave’s Marina, the only place on the Chain of Lakes to buy gasoline. It has been there since the end of World War II and is still run by the same family.

Lakeland’s biggest attraction was, and still is, the Zukey Lake Tavern, which opened when Prohibition ended. The original owners, the Girald brothers, used to take their motorboat down the Chain of Lakes, picking up passengers to bring them back to the tavern. Many customers still come by boat, and it’s a wonderful start or stop on any trip on the Chain of Lakes.

After World War II, construction of I-94 and US-23 made it easier to live on the lakes while commuting to work in Ann Arbor or beyond. Owners began winterizing their summer cottages or totally replacing them. Another big step toward year-round living came in the 1980s, when sewage systems began to be installed. In 2000 the Sallade cottage was totally rebuilt, so that Charlotte Sallade and her children and grandchildren can now enjoy it in any season.

Today almost all the rustic cottages on the Chain of Lakes have been improved or replaced. About half the residents commute to work—Ann Arbor is just a half-hour away, Lansing or Southfield an hour. Scott Strane, a thirty-year resident of Strawberry Lake, used to commute to a sports medicine job in Birmingham; he says he never minded, because “when we drive home every day, we are driving to heaven.” The people who don’t commute are mostly retirees who often spend the winters in warmer climates.

For people who want to relive the early days of the Chain of Lakes, Strane offers a three-hour tour on his pontoon boat. “Captain Scotty” models his itinerary on the original steam launch routes and narrates the history and natural wonders of the Chain of Lakes. He’s also willing to develop tours for special occasions. One cruise took members of a bachelorette party through the lakes, ending the tour, of course, with a meal at Zukey Lake Tavern.

Photo captions:

(Left) Dora Ware and other guests cruise the lakes in the Guthes' motor launch, 1917. (Below) visitors got to Lakeland on Zukey Lake via the Ann Arbor Railroad, then took to the water.

Ann Arbor businessmen and their families played poker and fished at the cottage built by brothers-in-law George Wahr and Charles Staebler on Base Line Lake.

The People's Ballroom: Seeing the Light, Taking the Heat

The first time I heard the term "politically correct," I was sitting on John Sinclair's bed. It was mid December 1972, and the week before, the Light Opera had put on a light show at the People's Ballroom.

I was seriously into doing lightshows at the time. Gather up some used slide and overhead projectors, mix well with colored oils and a variety of home-made psychedelic apparatus, and voila: a swirling visual treat just right to shine above a stage filled with sweaty rock and rollers. The Light Opera consisted at the time of myself, aided and abetted by Mike Lutz (not the rocker, the lab tech) and photographer Henry Seggarman.

Before the show I had borrowed my mom's camera and shot a bunch of logos of the Tribal Council, the umbrella organization through which Sinclair's Rainbow People's Party (RPP) supervised a host of countercultural activities-the Ballroom, the Tribal Network (the loose collective of the Ann Arbor Sun newspaper, and other media entities), the People's Defense Committee (which provided legal aid), and various other groups. Along with the logos, slides from the 1972 Blues and Jazz Festival, and the usual assortment of psychedelia, our show had featured my collection of tasteful classical nudes, garnered from my travels through the art museums of Europe.

That was what got us in trouble. I was being called to account before the Tribal Council's Music & Ballroom Committee, which met in the big house that the Rainbow People lived in on Hill Street. Sinclair's bedroom was the only meeting space available that day. Sinclair had come to town in the 1968 and formed the White Panther Party. By 1971, the year I graduated from Kalamazoo College and returned to Ann Arbor, the White Panthers had evolved into the Rainbow People's Party.

The on-line introduction to the John and Leni Sinclair Papers collection, now housed at the Bentley Historical Library, describes the party thusly:

"Rainbow People's Party embraced Marxism-Leninism as its guide to action and concentrated on building a strong local political organization to promote the revolutionary struggle for a "communal, classless, anti-imperialist, anti-racist, and anti-sexist...culture of liberation..."

The "strong local political organization" was the above-mentioned Tribal Council, and the Light Opera was up on charges of sexism.

The People's Ballroom wasn't owned by the Rainbow People. It shared a former Cadillac dealership with the Community Center Project, a federally-funded group of agencies consisting of Drug Help, Ozone House, and the Free People's Clinic. While the actual political ins and outs are too complicated to go into here (that would take a book, perhaps two), suffice it to say that the Ann Arbor Tribal Council Music & Ballroom Committee was a committee of dedicated lefties, and politics were never far from the matter at hand.

My own involvement was as non-political as I could make it. I saw myself as a simple artiste bent on photons and merriment. I was a child of the upper middle class (I grew up on the other side of Washtenaw from the Rainbow house, three blocks up Hill St.) and while of libertarian inclinations, I was in no way a radical.

Given John Sinclair's own legendary love of marijuana, his description of the Ballroom in a letter to the Musician's Union may seem surprising:

"Ann Arbor People's Ballroom is a non-profit, community-operated rock and roll dance center ... It has been funded under a federal grant designed to help combat the hard drug problem in Ann Arbor's rainbow community by providing activities and programs which give young sisters and brothers a constructive, positive context for their energy."

Note that Sinclair and the Rainbow folks (and almost everyone else in Ann Arbor) made a clear distinction between hard drugs (heroin, speed, etc.) and the non-menace of reefer. The Ballroom was at 502 E. Washington Street, where the Tally Hall parking structure is now. It was the result of years of planning, politicking, and involvement from the local hip community. Members of several local bands assisted in the construction, including the Wild Boys. I was in a band at the time, and remember making it to at least one of the pounding parties, after which we all went skinny dipping in Dolph Park.

The ballroom opened September 1st, 1972. The front offices held the various community center organizations and an open meeting room, and the ballroom was in the back, where the former Cadillac garages were. There was a continuing problem with street people hanging out in the meeting room, and a lot of discussion among the agencies as to how to deal with the issue. This would have serious repercussions, as we shall see.

The ballroom was around 100' wide by 40' deep, with a raised stage area at the east end and food and drink at the west end. A team of local volunteers had built an incredibly beautiful suspended dance floor for the Ballroom, and all were delighted with its dance-worthiness. The grand opening "tribal stomps" featured the Wild Boys, the

Mojo Boogie Band and Guardian Angel on Friday and Petunia (a jazz ensemble), Stone School Road, and the Rainbow People's house band, the Mighty UP, on Saturday. The total take was $928.50 and the place was packed, with lines out into the street.

The Ballroom had a total capacity of 540, was open Fridays and Saturdays, and was filled most of those nights. During the week there were art shows and other activities. I remember being at the Saturday opening show, and being blown away by how freakin' cool the whole thing was. Fillmore Ann Arbor! Just down the street from my church! (That would be the First Methodist Church, where I did time as Boy Scout, acolyte, and junior choir member).

Food was provided by the People's Food Committee, the RPP's Psychedelic Rangers provided security, and the Friday show was broadcast on WNRZ, the hip radio station of the time. In between bands, the Tribal Council Communications Committee interviewed musicians and community workers, and presented the whole ballroom story live on the radio.

The Ballroom became a must-play venue for bands across the state. At the Bentley Historical Library there are 76 boxes of cultural artifacts donated by John and Leni Sinclair from this era. In a folder called "Peoples Ballroom" are long lists of bands clamoring for dates, as well as the contracts for those bands that appeared. Also found are notes from Ballroom committee meetings, on which some of this story is based.

Dr. Arwulf Arwulf remembers the People's Ballroom

My most enduring memory of the People's Ballroom is of Mighty Joe Young's Chicago Blues Band. This was so different from anything us young white kids had ever experienced before. To stand in close proximity to this powerful blues engine, the punchy percussion, the electric lead, rhythm and bass guitars augmented by a no-nonsense alto saxophonist who never removed his hat and a wild trumpeter who screamed and hollered with abandon, this changed me permanently, and I'm sure that everyone else present that night was similarly altered for life."

The man who set the building on fire was a black Vietnam War veteran who later admitted that he wanted to be a hero but then couldn't extinguish the blaze in time, having set it in a room filled with cans of paint and turpentine. Knowing he had some problems left over from the war, I was not surprised when I heard he'd inadvertently torched the place. There was something else that might have exacerbated his problems. I vividly recall a scrawny little southern cracker hassling the hell out of him for being black, only weeks prior to the fire.

We were all hanging out on the overstuffed furniture in the front of the Community Center and this little shit was making the most incredibly offensive comments regarding the man's beautiful dark brown flesh. I remember the look on the black man's face as he bottled up his anger, and the tension I felt in the air, it was suffocating. His white girlfriend confronted the chump, angrily pointed out the fact that the individual he was hassling was a human being and ultimately chased the fool out of there.

On the wall of the Community Center was a big photograph of George Jackson. Peaking on my first acid trip after the last night of the Blues & Jazz Festival 1972, I'd stood in front of that picture for about an hour. Contemplating it again once the racist knucklehead had left the building, I remember asking myself why this poisonous racism was sullying our socially progressive space. It was a reminder that we all had our work cut out for us. And we still do."

--Dr. Arwulf Arwulf

The Ballroom was custom-made for light shows, so naturally we wanted to do a show there. My connection in was a high school student named Hugh Hitchcock, who was a phenomenal Moog synthesizer player. He had a band called Pyramus and I got them a gig at the Ballroom on 12-8-72 with the proviso that the Light Opera would accompany them.

To reach the Ballroom, you walked down the alley between the wings of the main building and entered through a small ticket-taking enclosure. Atop the enclosure was the area for the lightshow crew, accessible via a ladder. Which meant we had to pass up all our heavy projectors, slides, and other equipment before the show, hauling it all down thereafter. We had a wheel with holes in it spinning in front of the slide projectors, so we could flash the slides through colored filters, and the slides would flicker back and forth from one projector's output to the other. That way we could juxtapose nude females with nude males in a (to me, at least) humorous suitably-psychedelic fashion. And so, on the night Pyramus played, the first thing that greeted concert-goers was a big slide of the Tribal Council graphic, backed by naked people flickering in and out.

This, I thought, was pretty hilarious. But alas, I was politically incorrect. It seemed there was also a People's Lightshow Committee that I was unaware of, made up of a cadre of women who used to do lightshows at the Grande Ballroom in Detroit. Hard-core politicos, they didn't find our show funny at all.

They called us on it at the meeting on John Sinclair's bed. We (myself and Henry Seggarman) took a lot of flack from the cadre sisters (all the Rainbow people were brothers and sisters), who were incensed that we had the unmitigated audacity to feature naked women in our little presentation. The nude women in question were Aphrodite, the three Graces, and other alabaster figures familiar to anyone who has taken Western Art 101. The point was raised that nude men (Apollo, David, the Laocoön Group, etc.) were also involved, but somehow the cadre sisters missed seeing those.

There was much discussion of what was politically correct here, my first exposure to the term. There was much made of the idea that the show should reflect the community as a whole (as defined by the RPP cadre), not just be one group's (admittedly cockamamie) take on art and society.

At one point in the meeting, John's 5-year old daughter Sunny, wandered in looking for scissors. John asked her where they were the last time she saw them, and she said that John had them the last time, using them to cut up the peyote buttons. The upshot was that we got kicked out of the Ballroom. Which was a good thing, because the next week it burned down.

The Knock-Down Party Band and Merlin were on the bill for December 15, 1972, and a fire started in the basement. Everyone evacuated safely, and the bands even managed to get their equipment out. But the Ballroom and Community Center were toast.

According to the Ann Arbor Sun, the firemen pretty much stood by and let it burn. While it was certainly true that the whole operation, being of non-traditional brown rice longhair tie-dyed hippy origin, was not beloved by the local power structure, Joe Tiboni remembers the story a bit differently. He says the fire began in the basement of the front part of the building where the offices were (the Ballroom in the back was on a cement slab). When the firemen arrived, the fire, accelerated by silk screen solvent ("rocket reducer") used in the production of posters, had engulfed the entire ceiling and there wasn't anything anyone could have done.

I heard about the disaster the next morning when I went to pick up my week's food from the People's Food Coop. I was majorly bummed, as was the entire community. As I recall, the cause of the blaze was a very disturbed street person who hung around the Community Center. The story I heard was that he started the fire so he could report it and become a hero. He came running out of the basement yelling "Fire!" and grabbed the only fire extinguisher in the building. But the fire was already out of control and that was it for the Ballroom and Community Center.

Efforts were made to resurrect it, with concerts under the Ballroom name held in East Quad. The four main agencies at the Community Center, Ozone House, Drug Help, Free People's Clinic and the Community Center Project were housed temporarily at the former Canterbury House location on E. William St. Eventually all moved to more permanent quarters and all but Ozone House have long since been absorbed into other agencies or disbanded.

Disbanded as well was the People's Ballroom. It had a brief life; three and a half months of rock and roll, peace, love, and (mostly) understanding.

I took away from the experience a determination to continue my artistic tendencies, while avoiding contact with politicos as much as possible. I went on to play bass and guitar in a bunch of fun yet unsuccessful bands, doing lightshows until changing times made that impossible, and finally evolving to doing Mac computer support, web work, writing, and photography. And sometimes, when I take a digital picture, I think about how it would look flashing in colors above a band somewhere, with some nudes tossed in, just for grins.

Thanks Joe Tiboni for his insights and memories, and to Arwulf for taking the time to write down his recollections. And a big "Righteous, dude!" to John Sinclair for making the early 70's an interesting time in Ann Arbor, and for the foresight of donating his archives to the Bentley before his house in New Orleans burned down.

Below are photograph captions from the original print edition, also available from the author's website at: Mondodyne.

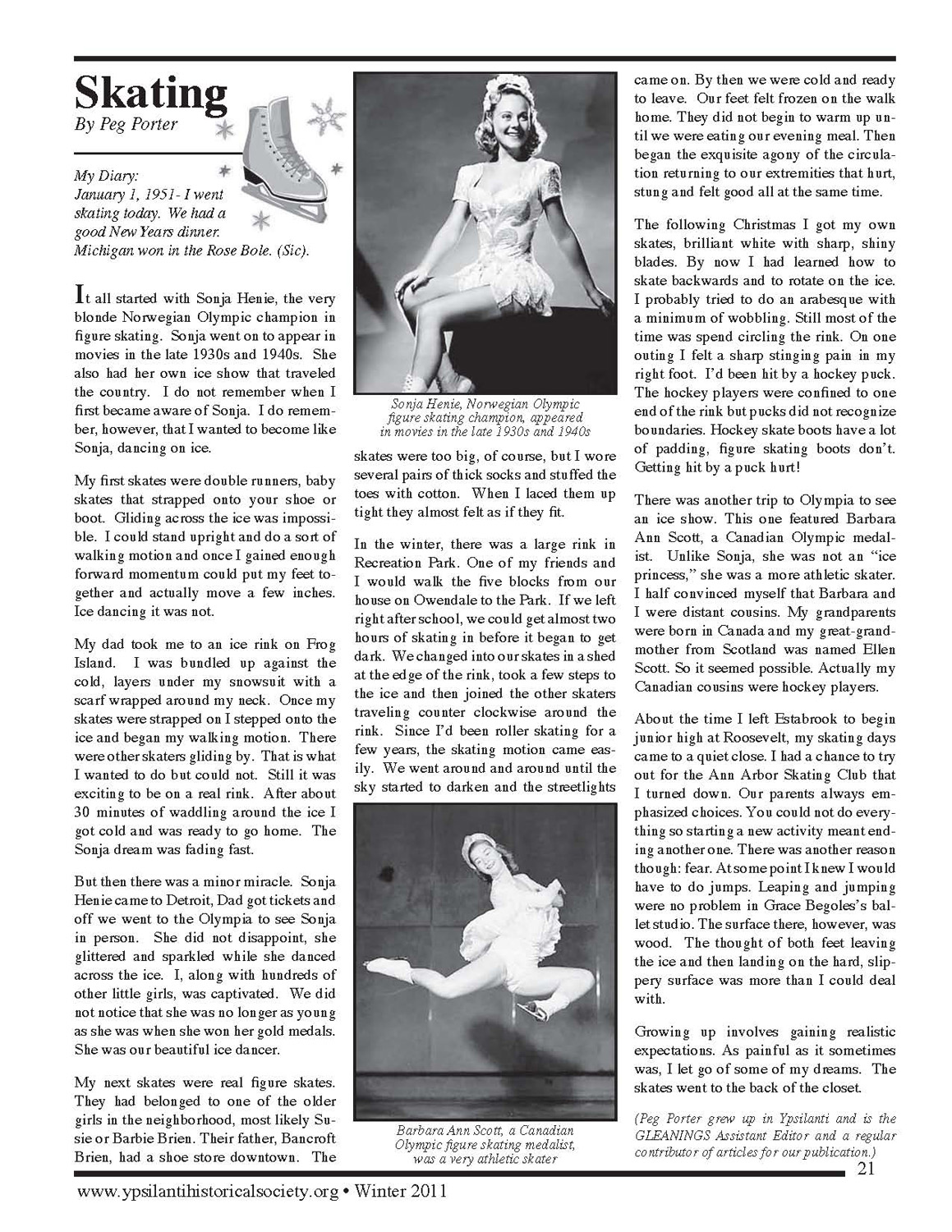

Caption 1: The picture above shows various Community Center members posed in front of the building before the renovation. This is from the Ann Arbor Sun newspaper, 7-27-71. According to Joe Tiboni, those pictured are: (On the left of the door) Laura [last name unknown], Matt Lampe, Joe Tiboni. (Right of the Door): Nancy Lessin (front row) Tanner, Michael Pollack, Robin Giber and Blue. Between Tanner and Pollack, Gayle Johnson. Others unknown. Photo by David Fenton. Photo courtesy of the John and Leni Sinclair papers, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

Caption 2: The photo above, taken during an art show at the Ballroom, shows John Sinclair on the left and Walden Simper in the foreground, flanked by Bob Sheffield (standing), others unknown. Photographer unknown, but probably David Fenton. Photo courtesy of the John and Leni Sinclair papers, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.